Lesson 51

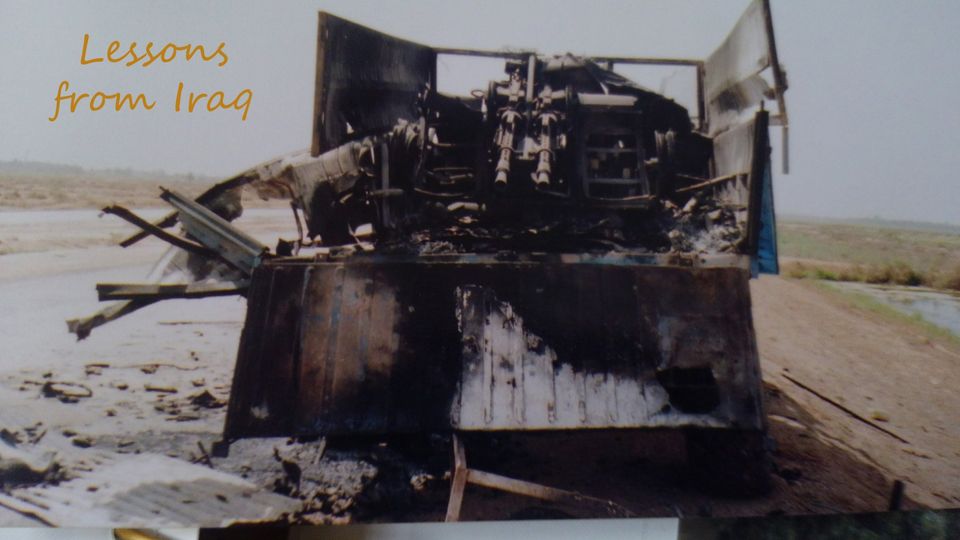

How would you like to be the guy sitting behind this thing trying to shoot down American aircraft?

Lesson 52

These things stay with you a long time.

Lesson 53: Real Scenario (from chapter 1 of Lessons from Iraq)

In the spring of 2003, out front of an abandoned bank a few miles south of Baghdad, Sergeant Stanley sat down to have breakfast in the passenger’s seat of his Humvee. Stanley was a short, thick-muscled black man who always wore a smile, treated everyone with dignity, and was quick to give his friendship. While Stanley was eating, an Iraqi man walked up to his Humvee, said “Good morning, mister,” drew a pistol, and shot him in the face.

Stanley should have died that day in front of the bank. The shot was point blank and he wasn’t wearing his Kevlar helmet. The bullet should have smashed straight through the spongy bone between his eyes. Instead, it ricocheted off his Oakley sunglasses and careened up his forehead, leaving only a graze wound and a muzzle burn the size of a quarter from the discharge of the round. After the shot, Stanley sprang out of his seat and shoved the Iraqi man, shouting, “Shoot him, shoot him, shoot him!”

In the short time it took the Marines in Stanley’s team to respond, the man cycled through his clip. The second shot hit Stanley in the chest, but his flak vest absorbed most of the blow. The third shot zipped through the open door of the Humvee, passing inches behind the neck of the driver and smashing through the window on the other side. The fourth shot bounced off the rifle hand guards of a Marine running from his post on the street to respond. The shots were good, and the Iraqi man was willing to die for what he believed, but he didn’t accomplish his purpose. Seconds after the man began firing, seven bullets passed through his body, fracturing and tearing as they went. The man fell to his knees and swayed. A corporal from Stanley’s team stalked up behind him, leveled his muzzle at the back of the man’s head and squeezed the trigger, painting the street with brains and bits of skull fragment.

Stanley re-gathered himself and went back to work.

Lesson 54

You’re a shepherd in southern Iraq. You’ve had a long day grazing your sheep through desert nothing, and you just don’t want to walk anymore. How do you get your flock home? No problem. Just take a bus.

Lesson 55

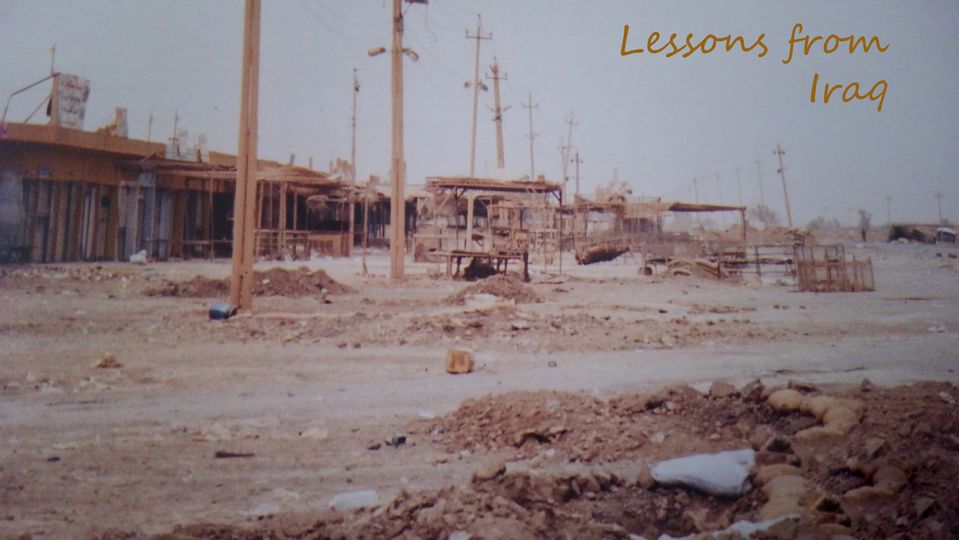

It’s amazing how much of Iraq looks like this.

Lesson 56

A few weeks into the war this is how we all looked, crusty muck covered chemical suits, head to toe sweat and grunge, showers and beds a memory from a different life.

Lesson 57

Something about camel spiders is just wrong. Besides corpse faces, these are the only things I ever had dreams about.

Lesson 58

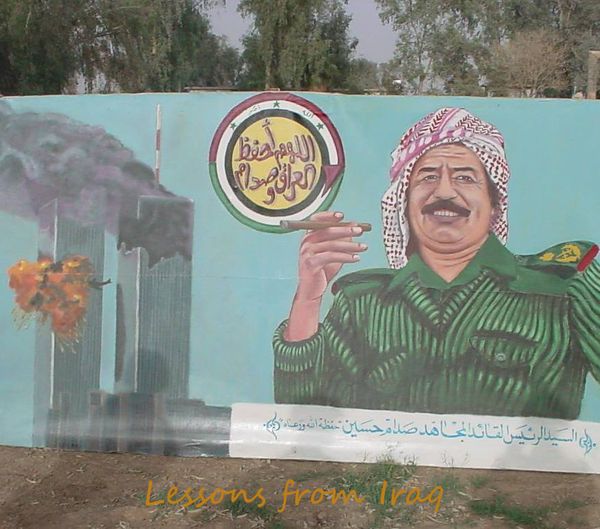

Saddam Hussein didn’t do himself any favors. After the World Trade Center was destroyed in 2001, Saddam’s advisors suggested that he send condolences to America. Instead, he broadcast praises for the attackers across national radio and had murals made commemorating the event.

Lesson 59

“Come outside, the weather is fine!”

Lesson 60

Private Schmuckatelli spots an Iraqi soldier. He won’t get away this time.

Lesson 61

The road is closed.

Lesson 62

You get used to the char on vehicles. The char on humans affects you differently.

Lesson 63: Real Scenario (from chapter 1 of Lessons from Iraq)

I’ve been in Iraq about a month, and a bear of a man approaches me. I’m working crowd control, turning away Iraqi civilians who want to get home past our roadblock. Heavy attacks are raging a few miles ahead and we don’t want civilians there. We don’t want dead civilians. As the man gets closer, he makes me feel small, frail. He’s full-grown, thick-chested and heavy through the gut with a jet-black beard and fury in his eyes. I’m just a kid, nineteen, not knowing exactly why I’m here or what I believe but wanting to do the best I can.

The man frantically points at an exploded blue hatchback just past our checkpoint. I can’t understand him, but he’s insistent, so I get our translator. The man says the blue hatchback is his brother’s car, and his brother has been missing for a couple days, so we allow him through the checkpoint. When the man gets to the car, his fears are confirmed. His brother is in two pieces, blown in half just above the hip. His torso lies face down and would be choking on sand if his lungs could still draw breath. His lower spine and blood-crusted legs are still plastered to the driver’s seat.

There are also two skeletons in the car, picked so clean by fire they look almost as if they’ve never been anything but bone, one in the passenger’s seat, and one in the back. A layer of glossy fat fused to the seat backs confirms that they were once something more substantial. The two skeletons are the man’s mom and dad.

When the bear-man realizes his entire family is gone, his howls come deep and guttural. His sounds are otherworldly, a kind of grieving I’ve never heard before. He lifts his heavy-muscled arms to the sky and seems to rave at God. I can’t understand his words, but his agony pierces the limitations of language. I watch the massive man crumble, feel myself crumble. I want to lend him comfort, to extend my hand and let him feel that he is not alone. We stand meters apart, but there is a wide gulf between us. I’m just a teenager in a strange land wearing the uniform of a foreign invader. It was likely at the hands of my people that his family was destroyed. Duty pulls me one direction, compassion another. Half of my heart goes with my body as I deal with the swelling crowd–we can’t lose control, can’t add violence to violence–half stays with the man as he scoops his family into a wooden box.

Lesson 64

The largest arsenal I’ve ever seen is what the US crossed into Iraq with in 2003. The second largest arsenal I’ve ever seen is what the Iraqi Army left on the side of the road.

Lesson 65

One of the tricky things about the war was insurgents using things they knew American soldiers would hesitate to search or engage, like shooting from mosques or transporting fighters and weapons in ambulances. They knew our ethics and used them against us when they could.

Lesson 66

Marine’s best friend.

Lesson 67

Not everyone is trying to kill you.

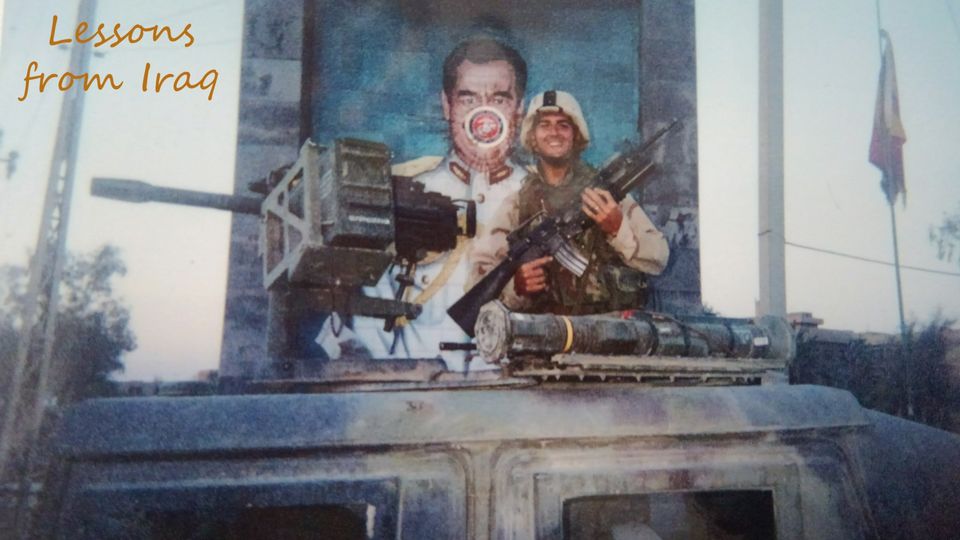

Lesson 68

Saddam in his perceived place in history among great Arab warriors.

Lesson 69

Because Saddam was always worried about being overthrown, he intentionally kept his military from being able to broadly communicate. Instead of a cohesive military working together, the Iraqi military was pieces here and there scattered all across the country. They had no chance.

Lesson 70

To all those who answered the call and paid the ultimate price, you have my respect forever. You were a different breed, sent by a country that no longer values honor, courage, and commitment, to do a job that became controversial after your deaths. You did that job to try to set a people free that couldn’t free themselves. No matter what the politicians said, no matter how the media spun it for selfish gain, no matter what the claims or criticisms of lesser men from the safety of their well-protected homes across the ocean, you were there. You know what it was like. You saw the people and did what you could. Until Valhalla.

Lesson 71

They sure love RPGs, but they’re not always the best at shooting them.

Lesson 72

Good times.

Lesson 73

Speeches from generals: “You are the greatest fighting force in the history of the world.”

Speeches from majors: “A lot of us are going to die tomorrow. Prepare for blood.”

Speeches from sergeants: “Alright, we’re here. Do your f***ing job.”

Lesson 74

He doesn’t have his blinker on.

Lesson 75

Flying into Kuwait City, pre-invasion February 2003.

Lesson 76

In 2003, there were mobilization camps like this all over Kuwait as 150,000 Marines and soldiers got ready to cross into Iraq.

Lesson 77

I see this picture and feel nervous. It brings me directly back to those weeks in Kuwait waiting for the order to invade, 19 years old, not knowing what was coming, running constant scenarios in my head.

Lesson 78: Real Scenario (from Lessons from Iraq chapter 9)

“VX gas is a nerve agent,” the Intelligence officer begins, my platoon sitting in a half circle in the sand at his feet. “It’s odorless, tasteless, and heavier than air. If you breathe it in, it’ll settle in your lungs and attack your nerve centers. Your muscles will seize, and you’ll fall to the ground, spasming until you snap your own spine. If your unit gets hit, go to MOPP level 4, and move to higher ground. Do not remove your mask or protective gear for any reason.”

This is a common briefing on the Iraq-Kuwait border in early 2003.

“Sarin gas is a lot like VX. It’s odorless and tasteless and attacks your nerves, causing paralysis of the muscles. Saddam used this shit in the 80’s on the Kurds, so don’t be surprised if he uses it on us.”

The last few weeks have been a blur. In mid-January, my MP unit got activated in Minnesota. After a flurry of dropping classes, cancelling leases, packing gear, and saying goodbyes, I’m on a plane to North Carolina, a plane to Germany, a plane to Kuwait. By early February, I’m in a desert camp preparing for the invasion of Iraq. Three weeks ago, I sat in a Midwestern college classroom listening to a sociology professor give another speech about men being pigs who do nothing but hold women down. Now I’m in a desert, with an Intelligence officer telling me that in a few days, I might puke up my lungs or snap my own spine.

“Mustard gas is a blister agent,” he continues. “It smells like garlic and onions. If it contacts your skin, your skin will bubble, and if you don’t die, you will be severely scarred. If mustard gas gets in your eyes, your eyes will swell in your head, and you’ll go blind. If you breathe it in, your lungs will blister, and you will vomit and cough up blood. Saddam used mustard gas on the Iranians in the Iran/Iraq war, and he used it on the Kurds in the 80’s. Don’t be surprised if he uses it on us.”

“Fuck, man,” Romero says, “I hope my dumb ass gets shot. This shit ain’t no way to die.”

“Nice clean shot to the head,” Baker says, “That’s the way to go. Not flopping around on the ground with my goddamn skin melting.”

“Phosgene gas and chlorine gas are both choking agents. Phosgene smells like fresh cut grass. Chlorine smells like bleach. Both attack your lung tissue. If you breathe them in, your chest will tighten, and you will hack and choke until you run out of air. Chlorine gas is cheap and easy to produce. Don’t be surprised if Saddam uses it on us.”

“At least we’ve got chemical detecting chickens,” I say. Romero and Baker snicker. A truck load of farm chickens arrived in camp the other day. They were supposed to be another line of defense, a gas detection system like canaries in coal mines. If gas was present, especially nerve agents we couldn’t see or smell, the chickens would die first and let us know to mask up and get the fuck out of there. Two days after the chickens arrived at camp, they were all dead. Apparently farm chickens don’t just die from chemical weapons. They also die from heat exposure and sandstorms.

Lesson 79

It’s better than breathing in poison, but it’d be damn near impossible to fight in all this rubber in 100+ degree heat.

Lesson 80

“Up in the morning with Iraqi sun”

Lesson 81

Training gets more intense the closer you get to your life depending on it. Almost “go” time.

Lesson 82

Hurry, hurry, hurry, wait for your plane. Hurry, hurry, hurry, sleep in a warehouse. Hurry, hurry, hurry, arrive in Kuwait. Hurry, hurry, hurry, live in a tent. Hurry, hurry, hurry, wait for the order. Go.

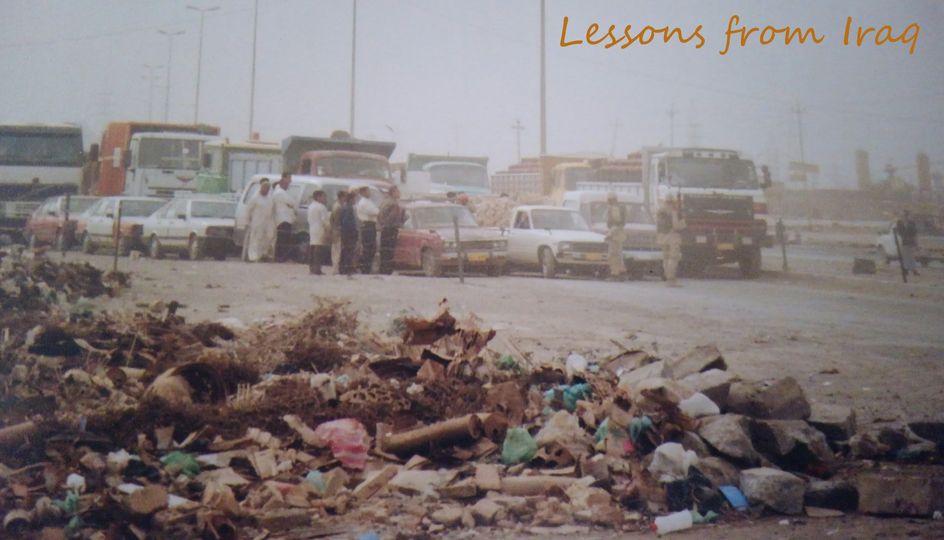

Lesson 83

There were millions of landmines in a “no man’s land” between Iraq and Kuwait. Many more landmines were hastily laid throughout Iraq by retreating Iraqi forces.

Lesson 84

We kept civilian traffic off the roads while military units pushed to Baghdad. Holding back a swelling crowd of Iraqi men and women while Abrams tanks zip down the road at 40 mph a couple feet behind your back is an unpleasant experience.

Lesson 85

Humvee life (1)

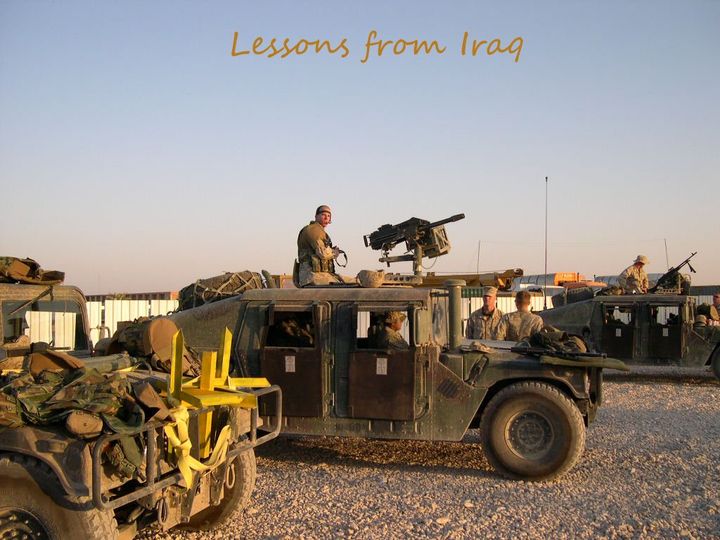

Lesson 86

We were invading soldiers, and imperfect as we were, people still came to ask us for help, to ask us to protect them from the remnants of their own government. Why? Because people coming from tyranny often understand America better than most Americans. They understand that even with America’s sins, even with its corrupt, self-serving leaders, even with its lack of understanding of how brutal much of the world really is, an American soldier will still spend their own blood for the freedom of others. That hasn’t changed. That’s what makes America unique. It’s something in the hearts of the common people that will not bend, something bestowed upon them by their Creator, a light that won’t be extinguished, a deep-seated belief, codified by their forefathers, that freedom to determine your own path is worth fighting for and, usually, suffering dearly for. There will always be greedy, cynical people willing to exploit this for their own gains. There will always be accusers without honor, unwilling to sacrifice for anything greater than themselves. But they can’t stop that thing in our hearts from existing. It runs too deep. It means too much. That’s what America means to me. That’s why it’s worth fighting for. God bless.

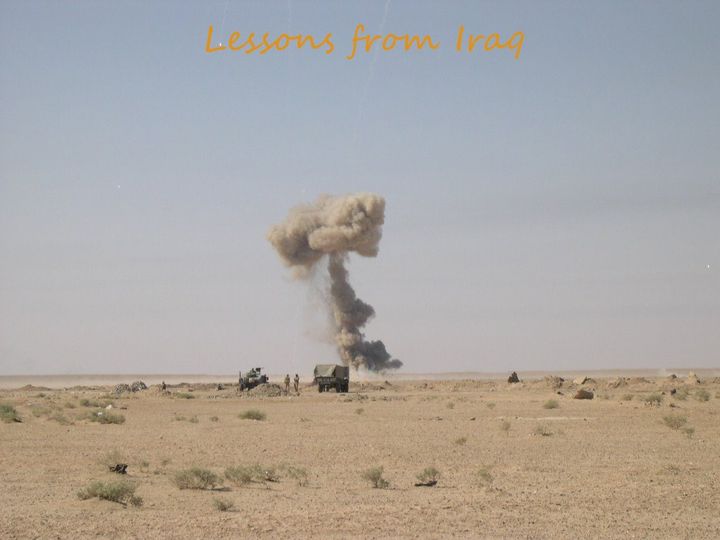

Lesson 87

It takes a couple weeks rolling up and down the roads behind a loaded machine gun for it to feel normal. Then it becomes as natural as breathing.

Lesson 88

Courtesy of the United States Marine Corps

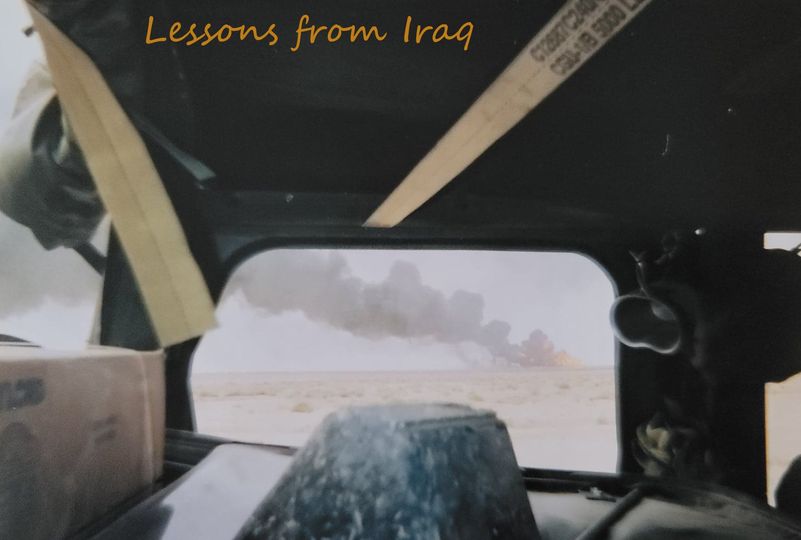

Lesson 89

It’s disturbing seeing smoke rise in the distance from something you did.

Lesson 90

Fodder for the boneyard.

Lesson 91

Expensive lawn ornament.

Lesson 92

Humvee life (2). Asleep not dead

Lesson 93

A few more things that go boom.

Lesson 94

Something in this picture looks out of place. I think it’s the moustache.

Lesson 95: Real scenario (from Lessons from Iraq chapter 3)

During the first Battle of Fallujah in 2004, my team was running convoy security on the roads between Ramadi and Fallujah. One night after a mission, we had a couple hours free and stopped at the Ramadi chow hall to get some food. Inside, I noticed a haggard looking soldier, probably nineteen or twenty like me, sitting alone at a table, so I sat down next to him, and we got to talking. He had just come from Fallujah. His unit was in the middle of the city and a few of them had come to Ramadi to grab a shower, some hot food, and a few hours R and R.

I was curious about what was happening in Fallujah. I knew what I was told in briefings, that a large group of insurgents had come to Fallujah to make a stand, and Marines and soldiers were going house to house killing some and funneling the rest toward areas more advantageous to our forces. When we drove through the outskirts a few days earlier, I saw Humvees cordoning off the city and American helicopters patrolling the skies. But I was interested to hear from someone on the ground. The soldier and I talked for about twenty minutes. He told me about troop movements, enemy fortifications, and an enemy tank his unit unexpectedly found dug in in the city. He looked worn out as he spoke about what he was going through, and even more worn out when his guys showed up and told him it was time to go back.

A few minutes after my conversation with the soldier I watched a news broadcast from a major American network. The anchorwoman came on with the words “Battle of Fallujah” written at the bottom of the screen in big letters. It was a high-level production—official looking maps, quality graphics, smooth cuts to live action sequences taken somewhere in Iraq. But as the anchorwoman spoke, not a word of what she said was even close to what the young soldier had just told me. Not a word of what she said matched what we’d been briefed on or what I saw driving through the city a few days earlier. I always wondered after that what the American people were even seeing at home.

Over the years, I’ve been surprised at how little people actually know about what happened in Iraq. It’s disturbing to me how information gets shaped to make people think certain things. A few chapters of this book are dedicated to addressing that issue. People need some context.

Lesson 96

Spring break Iraq: blue skies, endless sand, and the occasional barrage of hellfire missiles.

Lesson 97

The concussion blast goes right through your chest. It’s like a punch in the heart.

Lesson 98

Strolling through a graveyard.

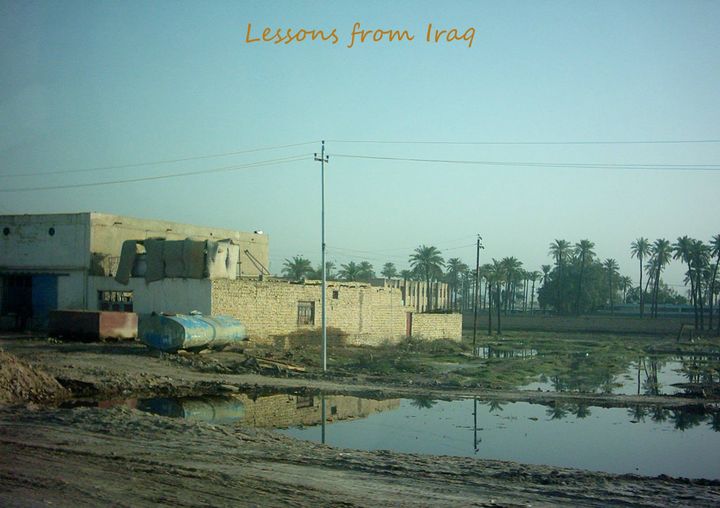

Lesson 99

Getting into the wetlands

Lesson 100

The view from the passenger’s seat.